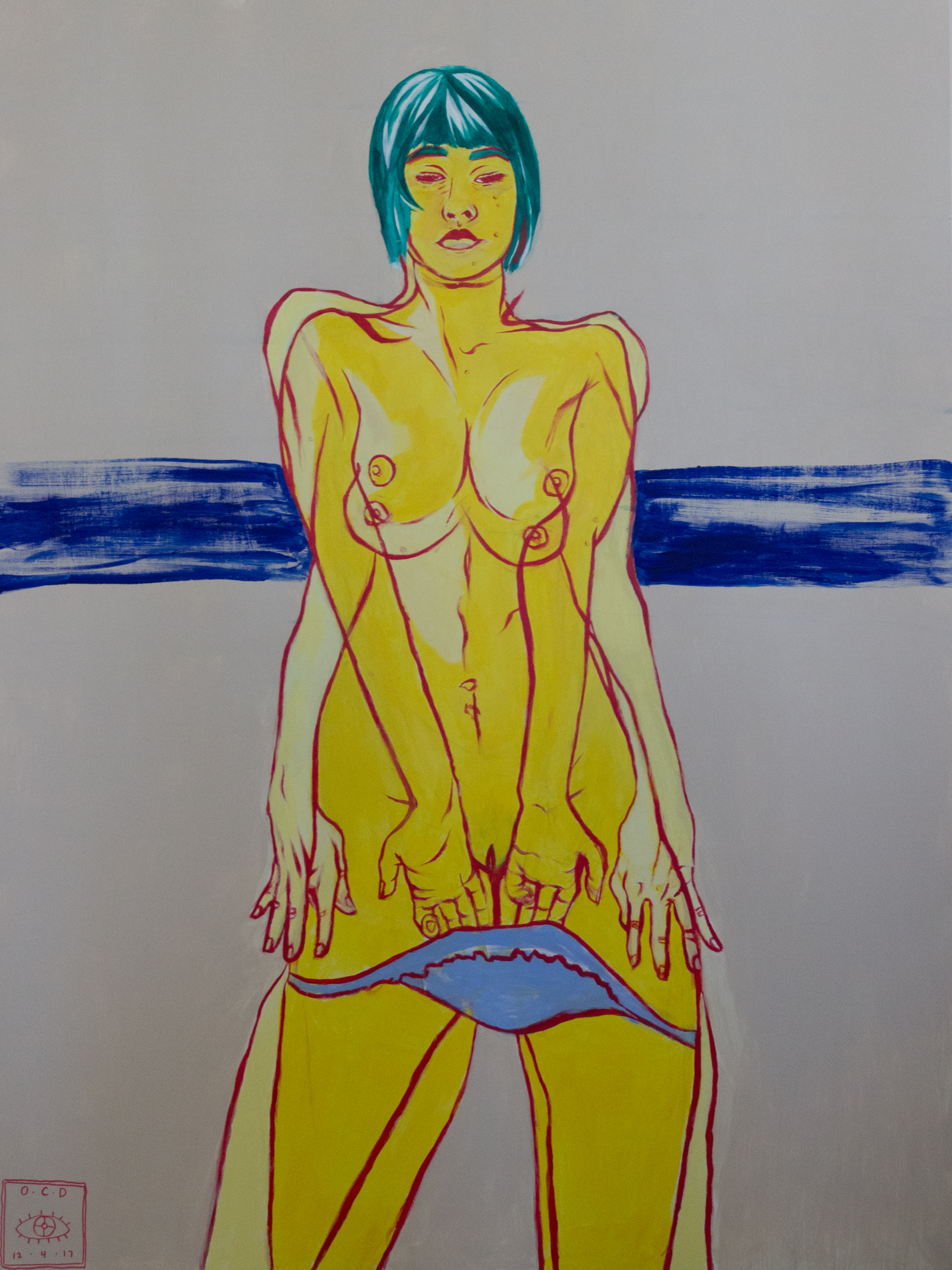

The intent of this piece is to help show the mental traumas that survivors of sexual assault go through and the bravery and strength they have in overcoming their experiences. I hope to also reinforce the idea that through all the ups and downs, the moments of strength and the moments of doubt, they remember that they are valid, empowered, and strong.

Dear Reader,

Welcome to MVMENT! MVMENT is a publication about gender and sexuality inequality, including sexual assault, sexual harassment, discrimination on the basis of gender or sexual identity and more; it is run entirely by students, for students, on high school and college campuses across the country. We believe that by engaging with these issues from a multitude of perspectives—including survivor stories, opinion pieces, investigative journalism and visual art—we can be better equipped to combat the systemic inequities our society has too easily normalized.

This first issue represents the yearlong work of dedicated individuals to make MVMENT a reality; despite numerous obstacles, it was ultimately the perseverance of our editorial board, liaison groups and contributors that made this possible. To them, I am incredibly grateful.

The following pieces are all student-created, and many are difficult to read. That is intentional. They explore the rawness of rape culture, gender identity and sexuality inequality. While the first issue focuses primarily on opinion pieces and survivor stories, subsequent issues will include a balance of journalistic pieces as well. Before we ask you to engage with these pieces, however, it is important that you know how MVMENT came to be.

MVMENT was conceived in late 2016. Leading up to that point, news outlets had written articles about sexual misconduct cases at multiple New England schools, and for the first time I realized these communities had elements of rape culture. It was no longer something I read about in the news or statistics presented in health class. It was local. It affected people I knew. As Facebook exploded with long expositions about the articles and the climate on campus, written by mostly upperclassmen, I realized how woefully unprepared I was to engage in the conversation. I didn’t know what to say, so I tried to listen.

Hearing friends recount their stories, from being catcalled while walking down the sidewalk to being raped at a party by someone they considered a friend, made the issue human. I had been at similar parties; I had watched absentmindedly as young girls got whistled at by middle-aged men as they walked down the street; but I never said anything. Why?

It might have been childish ignorance, absent mindedness or just the expectation that if something was wrong, surely others would take action. Regardless, it was inexcusable. And the more I listened, the more I realized that I had been a proponent of this culture. By taking part in conversations that blatantly objectified my fellow classmates, high-fiving the senior down the hall who had “scored” with two girls that week and sitting in silence while friends called each other “gay” like it was a bad thing, I had helped foster a toxic culture. I hadn’t knowingly become a supporter of such a society, but like most, I was ignorant about the impact of my actions.

There were many students, however, whose voices were yearning to be heard. Facebook posts had became a platform for individuals to share their views, ideas and experiences, and the comments became a forum for heated debate. But while there were many who posted, many more stayed silent about their experiences. I saw potential for a collaborative space between high school and college students, across all campuses, demographics and locations, dedicated to fostering a bigger discussion about gender and sexuality inequities. A publication meant to challenge our understandings, help us vary the lenses through which we see these issues and better empower us to be effective allies. Out of this, MVMENT was born.

It was ambitious, to say the least, but important to us that it be done properly. I reached out to Will Soltas (‘18) and Emily Robb (‘17) to be part of the initial Executive Board, and we began building the infrastructure in August 2016. Unfortunately, MVMENT fell apart that December, but it was because of that initial groundwork that we were able to pick up the year after. Both Will and Emily believed in MVMENT and devoted their time to bring a very abstract idea closer to reality. Although you may never know them, it is important for me to mention that without them, MVMENT would not exist as is does today.

Within the past two months, we created our editorial board, comprised of 19 individuals, and a liaison network spanning over 20 schools and consisting of over 70 students. We hope to keep expanding into more high schools and colleges across the country. You don’t have to be a survivor to contribute—anyone with a voice, story or opinion to share is welcome. We are not affiliated with any school or organization in order to stay impartial and true to the stories and news that we report. We stand together as a part of one larger community.

It is only by taking the responsibility upon ourselves to learn from each other’s experiences and engage in honest discussion that we can challenge the status quo. We ask for your help, readers, to create a meaningful shift in the way we treat each other. Give each piece the thought and respect it deserves. These works are emotional, terrifying, moving, disturbing and graphic; but they are necessary. Some are anonymous, but they are also written by your friend, or the girl who sits next to you in class, or your brother, or your girlfriend. These are stories that have been too long silenced; now, they need to be heard.

Examine your own role in perpetuating this system. It will be uncomfortable, but it is crucial. Without challenging our own views and the actions of those around us, we are contributing to a toxic environment—not by malice but by ignorance.

Read, engage and discuss. This culture can only survive in silence.

Yours,

Vinayak Kurup, Editor In Chief