Dear Reader,

It is my belief that we are currently experiencing a defining moment in history. Eight days ago, on October 6th, Brett Kavanaugh was sworn into the United States Supreme Court where he will preside over cases whose outcomes affect millions of Americans. With a majority conservative panel, many fear that the Supreme Court will now set precedents that strictly limit the rights of women, individuals of the LGBTQ+ community and other already marginalized groups. The landmark case Roe v. Wade and the reproductive rights granted to women in America as a result have been put in the national spotlight in the past months as many fear they will soon be overturned.

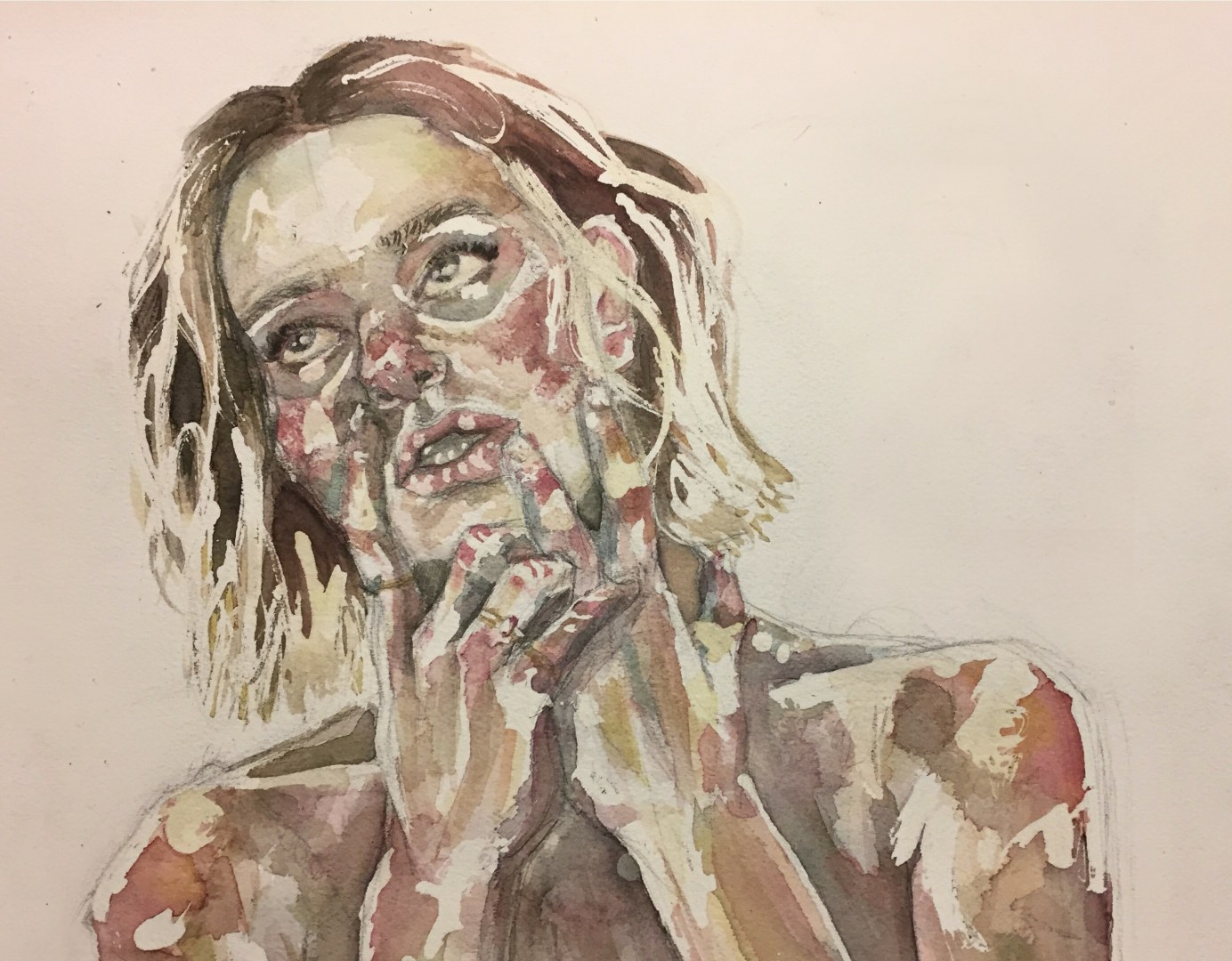

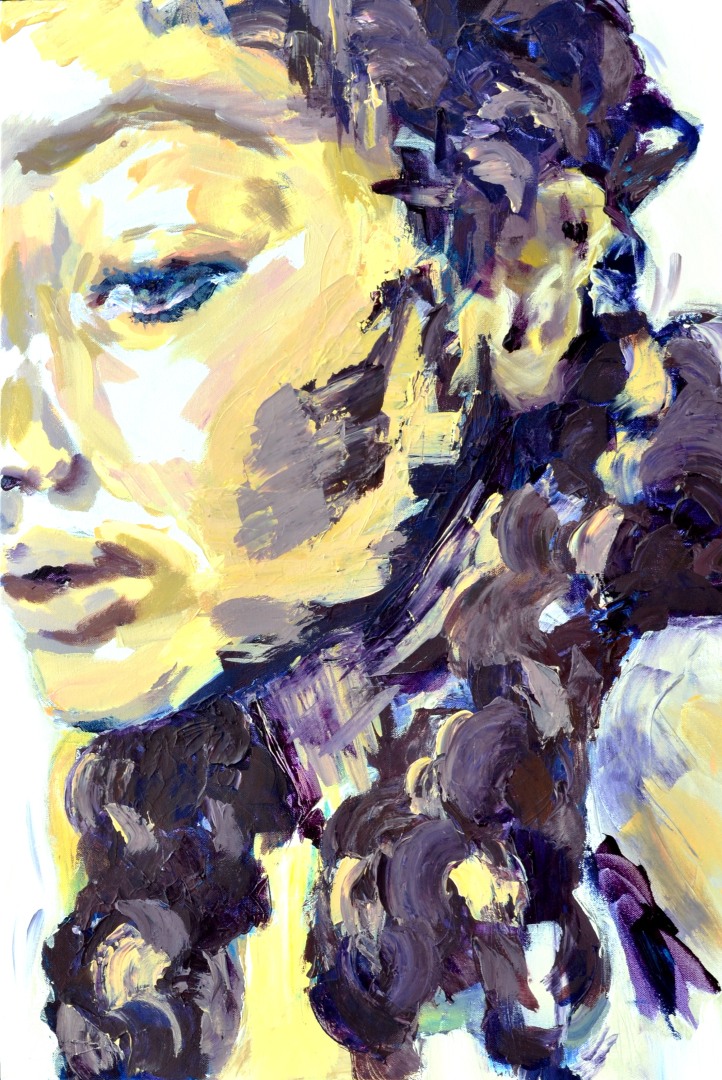

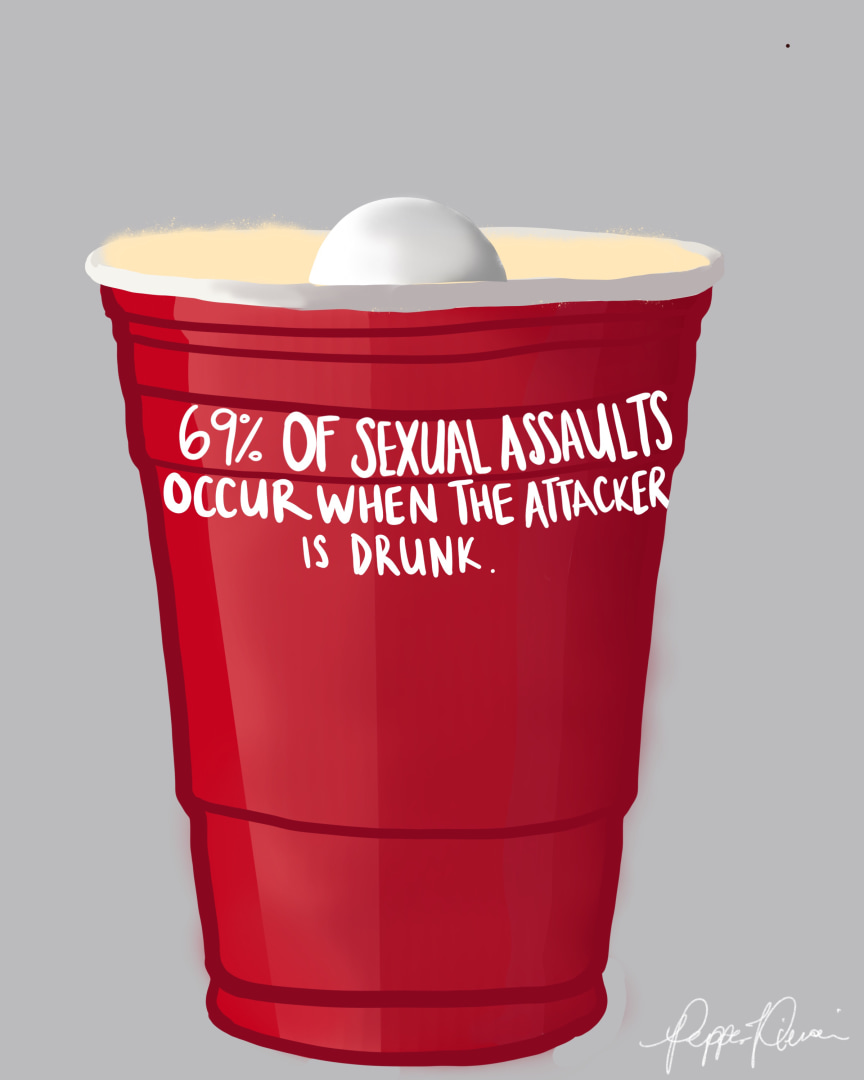

For the first time in MVMENT’s history, we decided to pinpoint a focus for our issue: Roe v. Wade, and more broadly, the state of reproductive rights. While not every piece in this Issue is related to this theme, understanding the systems currently in place is vital to changing the status quo and to reforming a larger culture of marginalization, not only behind closed doors and in the dark corners of college parties, but also out in the open, all around us. Our goal has always been to improve with every issue, aiming to find a way to tackle issues of gender and sexuality not only through a variety of perspectives, but also using many different mediums. Issue 6 is another step towards finding that balance, with more current events and investigative journalism pieces than any previous issue. We believe that emphasizing specific themes in this issue developed more depth and cohesion than we have had before.

In many ways, it seems inappropriate for me to write anything more personal about Kavanaugh’s confirmation that to say that I am disgusted. As one MVMENT staffer frankly put it: “you’re a straight, cis-gendered dude; your freedoms are safe.” She is right. I am not worried that my right to marry, start a family or buy contraception will be taken. I am not worried that I will be too young, too underprepared, yet left with no option but to have a child I cannot take care of. I am not afraid because I am a straight, cis man living in a system built by straight, cis men who find it easier to cast aside the shouts of millions than confront the broken system we have created.

During Justice Kavanaugh’s confirmation, three women came forth with accusations of sexual misconduct, and Dr. Christine Blasey Ford testified before the Senate judiciary committee. Her emotional account of being sexually assaulted at a highschool house party stands testament to the strength it requires to speak up. It shows us the power of our voices to ignite discussion, unify millions and empower victims to know that they are not alone. When you read the pieces in this issue, remember that these are highschool and college students. The girl who cried in her car before getting her abortion may be your classmate. The teen who woke up to find her friend’s older brother assaulting her might live down your street. To those who dismiss statistics, pay attention here. Pay attention to the narratives of these students whose voices you may already know.

The work we do is more important now than ever. For those who read Issue 6, post on social media, share these pieces with your classmates, your friends, your sports teams and your families, because it is time to confront these issues and drive change. To those who can vote, Midterm elections are November 6th. Please go out and make your voice heard by casting your vote—it really does matter. Finally, for those who are interested in getting involved with us, we are currently looking for passionate and accountable students as we continue to expand as an organization. We have 10 different groups, ranging from writing to illustrations to coding to PR/marking/outreach and many more in between. For those who are interested in getting involved with us in any capacity, or curious to learn more about our operation, the board positions, submission process, and more, please email gwilliams@mvmentmag.com.

I’ll conclude with a message I wrote and sent to the entire MVMENT Board minutes after learning Kavanaugh had been confirmed by the Senate:

Like many of you, I am sad but not shocked by the Kavanaugh confirmation. For those of us who watched Dr. Ford’s incredible testimony, her strength and tenacity will remain an inspiration to the work we do and survivors across the country. I am writing this immediately after finding out, and frankly I can’t quantify all of the thoughts going through my mind. The work we do now is more important than ever, because even if Dr. Ford’s testimony and the two other brave women who came forward weren’t successful in changing the vote, they told the truth and impacted millions of us across the country. In today’s world, I believe the conversations we have, the people we empower and the work we do is incredibly important in changing the dialogue about these issues. For many of you, the emotions you’re feeling are much more poignant and powerful because you directly are affected by this man’s appointment to the Supreme Court. We are here for you. We stand together. But we push forward, continue to broadcast voices that have been silenced for too long and demand the change we need to see.

Read. Engage. Discuss. The culture we live in can only survive in silence.

Yours truly,

Vinayak Kurup

Editor In Chief